America has a serious rural drug abuse problem.

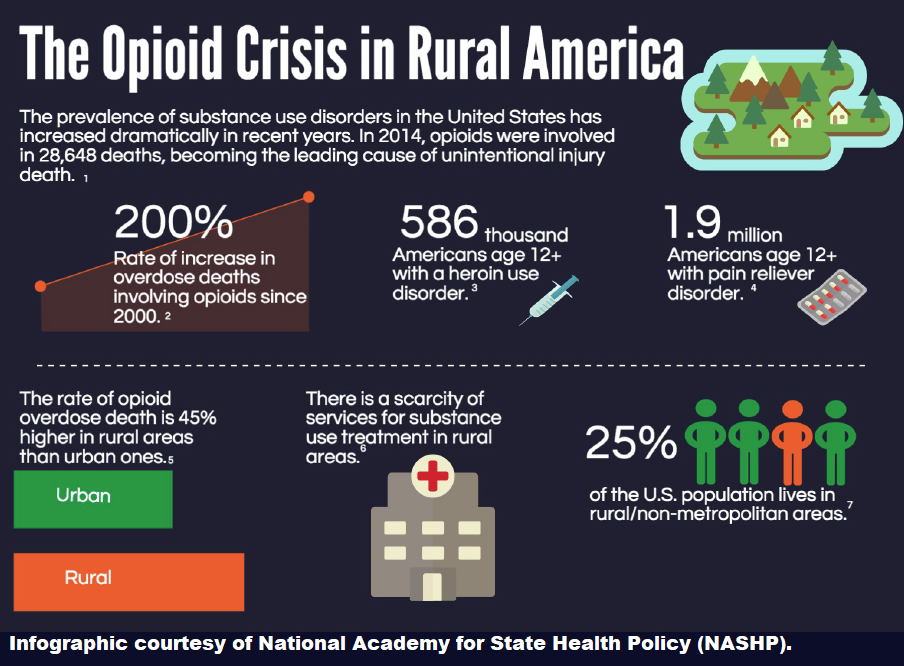

According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), overdoses from drug abuse in rural areas reached epidemic proportions in 2015. In fact, death rates from overdoses in rural areas now outpace the historically higher rate in large metropolitan areas.

The five states with the highest rates of death due to drug overdose in 2015 were West Virginia, New Mexico, New Hampshire, Kentucky and Ohio. And other states with significant increases in overdose deaths also have large rural populations: Alabama, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Maine, North Dakota, Pennsylvania and Virginia.

The five states with the highest rates of death due to drug overdose in 2015 were West Virginia, New Mexico, New Hampshire, Kentucky and Ohio. And other states with significant increases in overdose deaths also have large rural populations: Alabama, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Maine, North Dakota, Pennsylvania and Virginia.

So, what’s going on?

It Started with Prescription Opioids

The origin of the recent drug abuse epidemic can easily be traced. It all started with the best intentions of physicians in the 1990s.

That’s when doctors began routinely treating chronic pain with new synthetic opiates. According to Dr. Carl R. Sullivan III, the director of addiction services at the West Virginia University School of Medicine, “In the mid-1990s, there was a social movement that said it was unacceptable for patients to have chronic pain, and the pharmaceutical industry pushed the notion that opioids were safe.”

By 2010, enough opioids were being sold to medicate every U.S. adult with five milligrams of Hydrocodone every four hours. For a month.

The following video clip highlights the particular problem with prescription opioids:

But what are the causes behind the dramatic jump specifically in rural drug abuse? Aside from the standard explanations of poverty and unemployment – which are also prevalent in urban communities — medical officials cite several inter-related causes for the drug epidemic in rural areas:

Employment Issues

Rural occupations are typically much more physical than urban occupations, greatly increasing the risk of injury.

Many rural areas (such as Appalachian Kentucky and West Virginia) are home to industries that induce chronic pain, such as mining and even farming. With physical injury comes prescription pain medications, which are typically highly-addictive opioids.

Many rural areas (such as Appalachian Kentucky and West Virginia) are home to industries that induce chronic pain, such as mining and even farming. With physical injury comes prescription pain medications, which are typically highly-addictive opioids.

Instead of risking job loss, injured employees often rely on the pain medications to numb the problem.

But addiction doesn’t go away when the prescription does. According to Tom Frieden, Director of the CDC, increased numbers of Americans are “primed for heroin addiction because they are addicted to or exposed to prescription opioid painkillers.”

Also, research has shown that rural counties in particular have faced job sector and industry shifts, as populations shift to meet the labor demands of changing markets. This has resulted in long-term economic deprivation, high rates of unemployment, and fewer opportunities for establishing careers with potential for upward mobility.

The end result is an out-migration of young workers. Which leads to the next cause of the rural drug abuse problem…

Aging Communities

Rural populations are typically older, have more chronic illnesses and more prescription drugs overall, which presents a common introduction to the slippery slope of opioid abuse. And sometimes, an overdose isn’t necessarily from pre-meditated abuse, but rather from taking a concoction of prescribed pills for various conditions all at once.

Availability

Availability

Family and friend networks tend to be strongest in rural areas, creating an easier distribution channel for the drugs.

CDC researchers have found that more than three out of four people who misuse prescription painkillers are abusing someone else’s prescription.

CDC researchers have found that more than three out of four people who misuse prescription painkillers are abusing someone else’s prescription.

In rural communities, that person is typically a family member. Substantial empirical evidence indicates that the main sources of illicit prescription opioids are parents or other relatives.

As if that weren’t enough, prescription drugs are more aggressively marketed in rural communities, such as Appalachia.

Prescription Drug Crackdown

Over the last several years, states have been cracking down on physicians’ ability to prescribe opioids. In fact, 10 states, primarily in the northeastern U.S., have enacted legislation that limits opioid prescriptions to seven days or less.

So rural residents who are addicted to the prescription drugs are left to search for an alternative. According to Brock Slabach, vice president of the National Rural Health Association (NRHA), “Once an addict runs out, there are few rural programs available to help them with the next step. What is available is heroin. It’s a completely vicious cycle.”

NRHA research associate John Gale echoes that sentiment. “We’ve interviewed people who didn’t have health insurance who are using heroin to manage pain because it was cheaper than buying a prescription.”

Treatment Options

But the sheer distance from addiction treatment may be the primary reason that rural areas see so much drug abuse. Abuse that can easily lead to an overdose.

Without easy access to treatment medications and health workers, rural addicts are not motivated to seek help. And even when they do seek help, they may not find it. As many states cut back on public health funds, some rural health workers are limited to providing addicts with the phone number for a drug abuse hotline — which can only do so much.

In addition, in overdose situations, first responders are vital to the outcome. Yet many rural emergency services lack the resources to respond quickly and effectively.

In addition, in overdose situations, first responders are vital to the outcome. Yet many rural emergency services lack the resources to respond quickly and effectively.

Rural EMS system staffing often relies heavily on volunteers and lower-skilled staff who usually do not have access to the necessary medications to prevent death. Rarely are highly-trained paramedics the first responders in a rural community.

Add to that the fact that waiting lists for rural residential treatment programs are consistently maxed out. Addicts often must wait weeks before a spot becomes available, and by then, they may have lost their motivation.

What’s Next?

Authorities speculate that pulling rural America out of its drug-induced nightmare will require a massive collaboration between all levels of government, philanthropic and other charitable organizations, healthcare providers, and various community partners.

Whether that can be done remains to be seen. In the meantime, the death toll continues to rise.

Sources: